No comments yetBy

Some readers may have encountered this sporty sunfish before. Thomas McGuane paints quick, passing images of the fish in his essay and story collections An Outside Chance and Gallatin Canyon. John Gierach even has a tale titled "Rock Bass" in his book Another Lousy Day in Paradise. I find it interesting to note that in both cases the rock bass is not so much a quarry, sought after like the bonefish or trout, as a literary device: an image of childhood experience in the writings of McGuane; a catalyst for rumination on one's sense of place in the example penned by Gierach.

Call me a sunfish bohemian (my call and response to the trout bum); I must admit I also wax reflective when discussing the rock bass. There is for the imagination the intriguing space this fish fills in the Centrarchidae family. Visually, it is the transition species between the smaller, multicolored sunfish and the larger, more streamlined black basses. Practically, it is one of the first fish many American anglers catch, if only by chance. And within me, it mingles natural curiosity with personal memory. When this mix is added to angling considerations, a rock bass ascends from the shadow of a submerged stone. The rise is quick... the strike, hard... the fly rod, bent... the day, sunny.

Tadpoles and Fancy Cane Poles

The contemplation of rock bass in season conjures up a cinematic fly fishing setting: the high water of spring has receded; the summer flow meanders clear and low; dry stones protrude from the water like mismatched teeth; variations of brown and green dominate the palette, seasoned around the edges by the yellow, white, and lavender filigree of wildflowers, all sprouting and blooming from the cracks between the rocks piled along the bank.

Dip below the pool's reflection of those flowers. The quantity of this stream ecosystem's biomass is as impressive as its physical beauty and diversity. Fleets of snails, shells hoisted up at a diagonal angle reminiscent of cement trucks, construct a crisscross of wandering roadways atop the submerged rocks where, underneath, the claws of crayfish, some as large as small lobsters, peek out, poised to pinch. A sculpin flushes, rockets across the pool, leaving a vapor trail of sediment in its wake. Along the edges, within swaths of translucent green algae, numerous scuds and nymphs cling and crawl. Scattered here, too, are numerous dark dots with gossamer tails wriggling at full throttle: tadpoles, newly hatched, displaying a youthful exuberance of effort in opposition to the clam's pace of their actual forward progress.

Yes, I have prized the rock bass and its home waters since I myself was a tadpole and, indeed, it was this particularly meaty hatch that first lured these fun sport fish to my hook and hand.

Some of the more memorable weeks of my youth were spent vacationing along Laurel Hill Creek, a southwestern Pennsylvania limestone stream, nestled in the Appalachian Mountains, which flows fast and rocky like a freestone stream. Its fertile, alkaline waters are lush with flora and fauna and a variety of game fish. Enter a fisherman named Jim — a close family friend, who frequently hosted us at his parents’ compound beside this creek. Their place offered a variety of outdoor activities to pursue, including fishing, and on one afternoon, while my parents practiced their target shooting with bows and arrows, he took me aside and asked if I wanted to fish for “rock bass” — a fish I had never before caught.

“Sure!” I said. I was as eager then as now to add a new species to my lifetime catch list. And there was something alluring about the name — ROCK BASS. The sound conjured up images of clean, heavy, water-swept stone and strong, muscled, fighting fish. Plus it had an added coolness. When printed on paper, the name read like the musical instrument and style I most aspired to play as a hip adolescent.

We could have just stepped down to the bank in front of the cabin and cast our lines, but Jim, an avid cross-country motorcyclist and outdoor sportsman, had a more adventurous plan: “Grab your gear, a couple of sodas, and follow me,” he said. “Oh, yeah, and bring along the empty coffee can sitting outside the rear door.”

“What for?” I asked.

“You’ll see.”

We hiked along the gravel camp trail for about a mile until it petered out into two swampy furrows roughly the width of a pickup truck. The ruts were full of still water. Two parallel bands reflected lime green algae sheen between the hummocks of high seeded grass. Jim paused at this point and motioned me to pay quiet attention. I did so as he stomped a booted foot upon the ground. The furrows erupted into two boiling springs.

"What the —” I said, catching myself.

“Tadpoles,” Jim said. “Ready your net and the can!”

I did, and we scooped up a good two dozen of the wriggling dark creatures in less than ten seconds. We put these into the empty coffee can, which with a little water now served as a convenient holding pen for the tadpoles. Jim pointed out some big, sun-bleached rocks through the trees, and he announced that this was our destination. How convenient, I thought, the fishing spot was right beside a free, open-air bait shop!

We clambered up the face of “Big Boy” — a Gibraltar of a boulder if there ever was one — that brought us well above the water. A large, inviting pool curled around more exposed stones below. We each attached a size 6 snelled hook to our 4x tippets, baited up, and dropped down our tadpoles into the pool. Two huge rock bass — ten-inchers — simultaneously raced up like two rockets flying in a parting V-formation. The fish swallowed both our baits as if they were two pieces of buttered popcorn.

This rock bass tactic was simpler than most: tadpole, on hook, drifted with the current until it met a hungry fish. Our fly rods, turned into fancy cane poles, helped us make pinpoint drops into the numerous swirls, eddies, and backwaters surrounding the three sides of “Big Boy” that touched the creek. There seemed to be more rock bass in that one hole than I could count.

“Wow, this rocks!” I said at one point, foreshadowing my future as a constant punster.

Hammer and Scuttle

The rock bass, Ambloplites ariommus, could be called "bottom bass" just as easily. The specie’s variegated, splotched, brassy brown coloration matches the hatch of its stony streambed lair with amazing accuracy. This stream-friendly sunfish, which also inhabits cool freestone lakes and reservoirs, swims such waters throughout the Northeast, Midwest, and southern Canada. Rockies have distinctive red “goggle eyes” and the same elongated mouth and body as the redbreast sunfish. Add up these features — rocky environment + excellent camouflage + elongated body + large mouth — and the observant angler will equate the rock bass with other robust game fish such as its big cousin, the smallmouth.

The physiognomy of the rock bass reveals that it is not a sipper of surface insects like the bluegill or pumpkinseed sunfish. The rock bass is, in fact, carnivorous, and when plump tadpoles are not dropping from the sky, this fish can be found near the bottom of the water column hunting for its favorite flavor — the crayfish.

To catch rock bass consistently, a fly fisher should first chose the most promising water. This fish, like any other, has its preferences: eddies and pools adjacent to partially submerged rock piles that are also near areas of the water bathed in sun. Rock bass are as likely to hold, cruise, and feed along the shady side of these terminator lines as they are current seams.

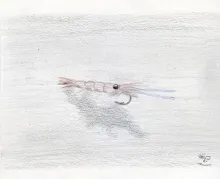

A fly fisher should next choose the right fly for the appropriate part of the water column. The bottom bass requires a weighted fly that resembles a crayfish or some other small dusky creature, such as a sculpin or goby, which scuttles along the bottom. “Scuttle” describes the action rock bass find irresistible. After the fly has been placed at the desired casting target and depth, an erratic retrieve that mimics the bottom bouncing antics of a spooked crayfish should commence. Time has proven three patent patterns most effective for this technique: Harry Murray's Strymph, Dave Whitlock’s “NearNuff” Crayfish, and Gordon Mackenzie of Redcastle’s excellent Deer Hair Freshwater Shrimp.

Mackenzie’s pattern has, for me, become the essential rock bass fly; one of those recipes that guarantee, at the very least, confidence along the water. I had the happy fortune to watch Mackenzie actually tie some of his patent Macored Hairys at one of the annual gatherings of The Fly-Fishing Show. He’s a friendly, patient Scotsman with bright white hair, and he maintains a very pleasant smile at the tying vise. I watched him apply dubbing fur in the manner he describes in his book Hair-Hackle Tying Techniques & Fly Patterns. In observing the motion, I perceived a link between the manufacture of these flies and the reason why the material is so effective when fished. This hair hackle dressing, like a finished fly made from it, undulates in the water. This seductive, full-bodied, head to foot wriggling motion plays well to the approach of the rock bass, and indeed all sunfish, which tend to stop, watch, and start, and then pause again before at last choosing to strike. The sight of undulating deer hair may stir a staring rock bass in the same way the motions of an exotic dancer can inspire an angler after a long day. I find it funny, in the ironic sense of the word, how a fly attached to a pole can be as alluring to a fish as a dancer attached to a pole can be to a fisher.

Short-line, high-stick nymphing is another fine way to present a sunk fly to rock bass. This technique also brings the fly-fisher closer to the quarry, which adds to the fun. A large Hare’s Ear, Woolly Worm, or Zug Bug pattern dropped with a minimum of fly line onto the slicks and sloughs around boulders can produce constant takes and large catches along a rock bass stream.

Rock bass hit a fly exceptionally hard, yet are not known as great, extended battlers for their size like bluegills and redbreast sunfish. I have come up with a theory for this contradiction. Observation strongly hints that the rock bass expends the majority of its fighting energy on the take. This fish will almost always stop and stiffen after a strike. This pounce and pause is done to stun or, in the case of hard-shelled crayfish, to crush its prey. The overwhelming wallop, as effective as it is, probably winds the rock bass, saps it of its strength, but the exciting hammer of that initial stunning hit more than makes up for its lack of endurance at the end of a line.

I have been an amateur musician for many years, comfortable on both keys and strings, and to use an analogy from that facet of my life I will state that, to me, the rock bass is akin to a punk rock song — It hits you hard, is pugnacious and tough up front, and though it doesn’t last too long, it is undeniably a strong, clever, and classic rocker.

The Rock Bass Kit

Basic Rig

5-weight fly rod and reel outfitted with floating line.

Fly Box

1) Gordon Mackenzie of Redcastle’s Deer Hair Freshwater Shrimp, size 10, 12

2) March Brown Wet, size 10, 12

3) Murray’s Strymph, size 8, 10

4) Whitlock’s “NearNuff” Crayfish, size 8, 10

5) Zug Bug, size 10, 12

Other Necessities

Insect repellent, medium landing net, non-toxic split shot, polarized sunglasses, wading staff.

- Log in to post comments

Some readers may have encountered this sporty sunfish before. Thomas McGuane paints quick, passing images of the fish in his essay and story collections An Outside Chance and Gallatin Canyon. John Gierach even has a tale titled "Rock Bass" in his book Another Lousy Day in Paradise. I find it interesting to note that in both cases the rock bass is not so much a quarry, sought after like the bonefish or trout, as a literary device: an image of childhood experience in the writings of McGuane; a catalyst for rumination on one's sense of place in the example penned by Gierach.

Call me a sunfish bohemian (my call and response to the trout bum); I must admit I also wax reflective when discussing the rock bass. There is for the imagination the intriguing space this fish fills in the Centrarchidae family. Visually, it is the transition species between the smaller, multicolored sunfish and the larger, more streamlined black basses. Practically, it is one of the first fish many American anglers catch, if only by chance. And within me, it mingles natural curiosity with personal memory. When this mix is added to angling considerations, a rock bass ascends from the shadow of a submerged stone. The rise is quick... the strike, hard... the fly rod, bent... the day, sunny.

Tadpoles and Fancy Cane Poles

The contemplation of rock bass in season conjures up a cinematic fly fishing setting: the high water of spring has receded; the summer flow meanders clear and low; dry stones protrude from the water like mismatched teeth; variations of brown and green dominate the palette, seasoned around the edges by the yellow, white, and lavender filigree of wildflowers, all sprouting and blooming from the cracks between the rocks piled along the bank.

Dip below the pool's reflection of those flowers. The quantity of this stream ecosystem's biomass is as impressive as its physical beauty and diversity. Fleets of snails, shells hoisted up at a diagonal angle reminiscent of cement trucks, construct a crisscross of wandering roadways atop the submerged rocks where, underneath, the claws of crayfish, some as large as small lobsters, peek out, poised to pinch. A sculpin flushes, rockets across the pool, leaving a vapor trail of sediment in its wake. Along the edges, within swaths of translucent green algae, numerous scuds and nymphs cling and crawl. Scattered here, too, are numerous dark dots with gossamer tails wriggling at full throttle: tadpoles, newly hatched, displaying a youthful exuberance of effort in opposition to the clam's pace of their actual forward progress.

Yes, I have prized the rock bass and its home waters since I myself was a tadpole and, indeed, it was this particularly meaty hatch that first lured these fun sport fish to my hook and hand.

Some of the more memorable weeks of my youth were spent vacationing along Laurel Hill Creek, a southwestern Pennsylvania limestone stream, nestled in the Appalachian Mountains, which flows fast and rocky like a freestone stream. Its fertile, alkaline waters are lush with flora and fauna and a variety of game fish. Enter a fisherman named Jim — a close family friend, who frequently hosted us at his parents’ compound beside this creek. Their place offered a variety of outdoor activities to pursue, including fishing, and on one afternoon, while my parents practiced their target shooting with bows and arrows, he took me aside and asked if I wanted to fish for “rock bass” — a fish I had never before caught.

“Sure!” I said. I was as eager then as now to add a new species to my lifetime catch list. And there was something alluring about the name — ROCK BASS. The sound conjured up images of clean, heavy, water-swept stone and strong, muscled, fighting fish. Plus it had an added coolness. When printed on paper, the name read like the musical instrument and style I most aspired to play as a hip adolescent.

We could have just stepped down to the bank in front of the cabin and cast our lines, but Jim, an avid cross-country motorcyclist and outdoor sportsman, had a more adventurous plan: “Grab your gear, a couple of sodas, and follow me,” he said. “Oh, yeah, and bring along the empty coffee can sitting outside the rear door.”

“What for?” I asked.

“You’ll see.”

We hiked along the gravel camp trail for about a mile until it petered out into two swampy furrows roughly the width of a pickup truck. The ruts were full of still water. Two parallel bands reflected lime green algae sheen between the hummocks of high seeded grass. Jim paused at this point and motioned me to pay quiet attention. I did so as he stomped a booted foot upon the ground. The furrows erupted into two boiling springs.

"What the —” I said, catching myself.

“Tadpoles,” Jim said. “Ready your net and the can!”

I did, and we scooped up a good two dozen of the wriggling dark creatures in less than ten seconds. We put these into the empty coffee can, which with a little water now served as a convenient holding pen for the tadpoles. Jim pointed out some big, sun-bleached rocks through the trees, and he announced that this was our destination. How convenient, I thought, the fishing spot was right beside a free, open-air bait shop!

We clambered up the face of “Big Boy” — a Gibraltar of a boulder if there ever was one — that brought us well above the water. A large, inviting pool curled around more exposed stones below. We each attached a size 6 snelled hook to our 4x tippets, baited up, and dropped down our tadpoles into the pool. Two huge rock bass — ten-inchers — simultaneously raced up like two rockets flying in a parting V-formation. The fish swallowed both our baits as if they were two pieces of buttered popcorn.

This rock bass tactic was simpler than most: tadpole, on hook, drifted with the current until it met a hungry fish. Our fly rods, turned into fancy cane poles, helped us make pinpoint drops into the numerous swirls, eddies, and backwaters surrounding the three sides of “Big Boy” that touched the creek. There seemed to be more rock bass in that one hole than I could count.

“Wow, this rocks!” I said at one point, foreshadowing my future as a constant punster.

Hammer and Scuttle

The rock bass, Ambloplites ariommus, could be called "bottom bass" just as easily. The specie’s variegated, splotched, brassy brown coloration matches the hatch of its stony streambed lair with amazing accuracy. This stream-friendly sunfish, which also inhabits cool freestone lakes and reservoirs, swims such waters throughout the Northeast, Midwest, and southern Canada. Rockies have distinctive red “goggle eyes” and the same elongated mouth and body as the redbreast sunfish. Add up these features — rocky environment + excellent camouflage + elongated body + large mouth — and the observant angler will equate the rock bass with other robust game fish such as its big cousin, the smallmouth.

The physiognomy of the rock bass reveals that it is not a sipper of surface insects like the bluegill or pumpkinseed sunfish. The rock bass is, in fact, carnivorous, and when plump tadpoles are not dropping from the sky, this fish can be found near the bottom of the water column hunting for its favorite flavor — the crayfish.

To catch rock bass consistently, a fly fisher should first chose the most promising water. This fish, like any other, has its preferences: eddies and pools adjacent to partially submerged rock piles that are also near areas of the water bathed in sun. Rock bass are as likely to hold, cruise, and feed along the shady side of these terminator lines as they are current seams.

A fly fisher should next choose the right fly for the appropriate part of the water column. The bottom bass requires a weighted fly that resembles a crayfish or some other small dusky creature, such as a sculpin or goby, which scuttles along the bottom. “Scuttle” describes the action rock bass find irresistible. After the fly has been placed at the desired casting target and depth, an erratic retrieve that mimics the bottom bouncing antics of a spooked crayfish should commence. Time has proven three patent patterns most effective for this technique: Harry Murray's Strymph, Dave Whitlock’s “NearNuff” Crayfish, and Gordon Mackenzie of Redcastle’s excellent Deer Hair Freshwater Shrimp.

Mackenzie’s pattern has, for me, become the essential rock bass fly; one of those recipes that guarantee, at the very least, confidence along the water. I had the happy fortune to watch Mackenzie actually tie some of his patent Macored Hairys at one of the annual gatherings of The Fly-Fishing Show. He’s a friendly, patient Scotsman with bright white hair, and he maintains a very pleasant smile at the tying vise. I watched him apply dubbing fur in the manner he describes in his book Hair-Hackle Tying Techniques & Fly Patterns. In observing the motion, I perceived a link between the manufacture of these flies and the reason why the material is so effective when fished. This hair hackle dressing, like a finished fly made from it, undulates in the water. This seductive, full-bodied, head to foot wriggling motion plays well to the approach of the rock bass, and indeed all sunfish, which tend to stop, watch, and start, and then pause again before at last choosing to strike. The sight of undulating deer hair may stir a staring rock bass in the same way the motions of an exotic dancer can inspire an angler after a long day. I find it funny, in the ironic sense of the word, how a fly attached to a pole can be as alluring to a fish as a dancer attached to a pole can be to a fisher.

Short-line, high-stick nymphing is another fine way to present a sunk fly to rock bass. This technique also brings the fly-fisher closer to the quarry, which adds to the fun. A large Hare’s Ear, Woolly Worm, or Zug Bug pattern dropped with a minimum of fly line onto the slicks and sloughs around boulders can produce constant takes and large catches along a rock bass stream.

Rock bass hit a fly exceptionally hard, yet are not known as great, extended battlers for their size like bluegills and redbreast sunfish. I have come up with a theory for this contradiction. Observation strongly hints that the rock bass expends the majority of its fighting energy on the take. This fish will almost always stop and stiffen after a strike. This pounce and pause is done to stun or, in the case of hard-shelled crayfish, to crush its prey. The overwhelming wallop, as effective as it is, probably winds the rock bass, saps it of its strength, but the exciting hammer of that initial stunning hit more than makes up for its lack of endurance at the end of a line.

I have been an amateur musician for many years, comfortable on both keys and strings, and to use an analogy from that facet of my life I will state that, to me, the rock bass is akin to a punk rock song — It hits you hard, is pugnacious and tough up front, and though it doesn’t last too long, it is undeniably a strong, clever, and classic rocker.

The Rock Bass Kit

Basic Rig

5-weight fly rod and reel outfitted with floating line.

Fly Box

1) Gordon Mackenzie of Redcastle’s Deer Hair Freshwater Shrimp, size 10, 12

2) March Brown Wet, size 10, 12

3) Murray’s Strymph, size 8, 10

4) Whitlock’s “NearNuff” Crayfish, size 8, 10

5) Zug Bug, size 10, 12

Other Necessities

Insect repellent, medium landing net, non-toxic split shot, polarized sunglasses, wading staff.

- Log in to post comments